JACKSON, Miss. — Marquita Moore was lying on her sofa at home on the night of Oct. 10 when she got a text from her aunt. It was a link to an article revealing that Jackson police had failed to notify the public about dozens of homicides this year.

Marquita clicked on it, wondering why her aunt thought she’d be interested.

Then she scrolled to the list of 24 homicide victims.

The second name was her older brother’s. Marrio Terrell Moore, 40, had been killed on Feb. 2, the article said.

This was news to Marquita — and to the rest of her family.

She shuddered and started to cry. “Lord, this is my brother,” she recalled saying aloud. “Someone done killed my brother.”

It was after 8 p.m., and she was in her pajamas. She put on a jacket and shoes and went to the Jackson Police Department’s downtown headquarters looking for an explanation. An officer told her no one was available, she said.

Over the next couple of days, Marquita and her relatives, dazed and stricken, gradually learned bits of information about what had happened and at each step grew angrier and more hurt.

Marrio had been bludgeoned to death, wrapped in a tarp and left on the street. For months, his body had lain in the Hinds County morgue, unclaimed. Then, on July 14, inmates at the county penal farm had buried his remains in a pauper’s field.

The news wrecked Marrio’s mother, Mary Moore Glenn, who has not come to terms with his death and what authorities did to his body without her knowing.

“What are you hiding?” Mary said in a recent interview. “Why can’t you just come and just tell somebody that their child is gone?”

Marrio was buried the same day and in the same place as Dexter Wade, a Jackson man whose death sparked public outrage and calls for a federal investigation when NBC News reported on it last month. Wade, 37, was struck and killed by an off-duty Jackson police officer while crossing a six-lane highway on March 5. Authorities failed to notify his mother, who reported him missing to Jackson police a few days later, and buried him without her knowledge. Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba has blamed a communication failure and expressed regret, but the city has declined to answer detailed questions.

Both cases expose failures of a system designed to ensure that families are notified when their loved ones die and are given the chance to claim their bodies.

Dexter Wade's story

- Wade, 37, was run over by a police cruiser in March and buried in Hinds County's pauper's field in July, without his family's knowledge.

- With assistance from attorney Ben Crump following NBC News' reporting, Wade was exhumed from the pauper's grave, marked only with a number, in November.

- A week later, civil rights leaders spoke at Wade's funeral and his family finally buried him in a cemetery.

In the days after learning about his death, Marrio’s family sought explanations from the Jackson Police Department and Hinds County coroner’s office. They recorded conversations with officials from both agencies and provided copies to NBC News. NBC News also obtained documents about the case through public records requests.

The recordings and documents show that authorities said they made attempts to contact Marrio’s family but did not do enough to find his mother and other relatives in Jackson who say they would have claimed him.

A Hinds County coroner’s office investigator said in a report that she called Marrio’s brother, but the phone number didn’t work. A police commander told the family that a detective left a card at Marrio’s mother’s house. But neither his mother, brother nor two sisters recall being contacted by anyone responsible for reaching his next of kin.

The coroner's office and the Jackson Police Department did not comment.

Marrio led an itinerant life and often went months without seeing his closest relatives, and so they did not report him missing in the months after he was killed. But the family says that should not have mattered; they were not hard to find.

“They just, ‘Oh, well, he ain’t got nobody,’” Marquita said. “And they just threw him away.”

Marrio, the oldest of five siblings and the father of an adult daughter, was loved by his family. He was humble and thoughtful. He worked maintenance and construction jobs and most recently collected shopping carts at a grocery store. He read a lot. He was able to talk to just about anyone about virtually anything: religion, politics, what was happening on the street.

That is what his family wants people to know about him.

“He was very smart and intelligent. He just happened to struggle with things of the world,” cousin April McNair said.

Marrio had a 20-year drug habit, and with that — perhaps because he had been raised in a devout Christian home — came feelings of guilt, his family said. He seemed in constant motion. He walked fast, like he always had to be somewhere. He moved around within Jackson and also, temporarily, to more distant places like Atlanta and Indiana. He was convicted of car theft and grand larceny. He rarely shared what he was up to or where he was going. He usually stopped by his mother’s house during the holidays to eat and talk and collect mail and then left. It was as if he didn’t want to burden anyone, including the people who loved him most.

“If you tried to get too close to him, he knew what he was doing and he knew somebody was going to tell him, ‘You need to do this or do that.’ So he stayed away for that reason,” said another sister, Marcedes Onuchukwu. “Because he basically didn’t want nobody, I guess, shaming him because of his choices.”

Still, his family tried to keep in touch. His mother, stepfather, aunt, uncle and siblings at various points this year looked for him or tried calling him, relatives said. They didn’t find him, but that wasn’t unusual. It didn’t occur to them to report him missing.

“He wasn’t missing. He just didn’t want to be found. He didn’t want to be seen,” Marcedes said.

The last relative to see him was Marquita, who ran into him at a corner store in January. She gave him $5 and told him to be careful, and he assured her that he would and quickly walked out of sight.

She assumed they’d all see him around Thanksgiving.

At around 10 a.m. on Feb. 2, a cold and rainy day, a man called Jackson police to say he’d come across a body wrapped in a tarp on Gunda Street earlier in the morning, according to reports by the Hinds County coroner’s office and the Jackson Police Department. The dead man had dozens of wounds to his face and head, including skull fractures, indicating that he’d been beaten. In one of the man’s pockets were wet envelopes addressed to "Mario Moore" and a debit card with the name “Mario Moore,” a deputy medical examiner investigator, Stephanie Horn, reported, recording a misspelling of Marrio’s first name.

The man’s body was taken to the county morgue, where the cause of death was determined to be homicide by blunt force trauma to the head. On Feb. 8, fingerprint records maintained by the state crime lab confirmed the man’s identity as Marrio Moore, the documents show. A search of medical records led to a number for a brother, whom Horn identified in her report as Gavin Moore. “The number was not a working number and the decedent remained unclaimed,” Horn wrote.

(Marrio’s family says that his only brother is named Godwin Onuchukwu and they’ve never heard of a relative named Gavin Moore. Godwin told NBC News he had never gone by the name Gavin.)

On March 31, the coroner’s office asked the Hinds County Board of Supervisors for permission to bury Marrio’s body in a pauper’s field at the county’s penal farm. On April 3, the board approved the request, along with similar requests for nine other bodies, including Dexter Wade’s, by a unanimous voice vote that lasted 12 seconds. The burial happened on July 14.

NBC News requested from Hinds County any records documenting efforts to notify Marrio’s next of kin. Those records do not indicate that the county did anything more.

Marrio’s family — including his mother, who has lived for 20 years in a house 2 miles from where his body was found and where he received child support bills and other mail — knew nothing about any of this.

Months passed.

On Oct. 9, the local NBC affiliate, WLBT, reported that the Jackson Police Department had just released the names of 24 homicide victims that had not previously been disclosed, including Marrio's. A commander told the station that it had been an accidental oversight and blamed a communications failure.

Marrio’s uncle, who works for the Hinds County Sheriff’s Office, saw the list and shared it with his wife, who texted the link to Mary, Marrio’s mother, and Marquita, his sister, on the night of Oct. 10.

The family’s first thought was to protect Mary. A grandchild snuck onto her phone and deleted the text so that they could break the news to her in person, once they knew more.

Then they started searching for answers.

On Oct. 11, the morning after Marquita had gone to Jackson’s police headquarters, she and Marcedes left a message at the county coroner’s office. Horn, the deputy medical examiner investigator, called them back, they said. The sisters asked why they weren’t told about their brother’s death.

Horn told them that the coroner’s office had shared information about Marrio’s identity with Jackson police. “It’s up to their detectives and everybody to reach out,” Horn said. (Horn could not be heard identifying herself on that recording, but she did identify herself on another recording the family shared.)

State law says that coroners “shall make reasonable efforts to notify members of the decedent’s family.” If a body goes unclaimed after five days, county authorities can bury it. The state Medical Examiner’s Office and the state Board on Law Enforcement Officer Standards and Training said they leave it to local agencies to develop specific policies on death notifications.

A Hinds County coroner’s office representative has said that it generally relies on police to notify the families of people who have been killed, and that investigators typically work closely with Jackson police on the process. At the time of Marrio’s death, the Jackson Police Department did not have a formal policy on death notifications. Jackson’s police chief recently said the department had enacted a new policy.

On the call with Horn from the coroner’s office, the sisters started by asking: Where was their brother's body?

Horn said Marrio was in “a massive grave," according to the recording.

“He’s buried already?” Marcedes asked.

“Ain’t no way,” Marquita sobbed. “Ain’t no way.”

When the sisters pressed her, Horn explained that Marrio's gravesite was in “an undisclosed location” where inmates and unclaimed people are buried.

To get more information, including an autopsy report and the exact location where their brother was buried, Horn said they would first have to go to Jackson police and provide proof that they were Marrio’s family.

After the call, the sisters said, they contacted their mother’s pastor and asked her to meet them at Mary’s home to deliver the news. When everyone arrived, Marquita recalled, she told her mother, “Marrio’s gone.”

“Girl, quit playing with me,” Mary replied.

“For real, mom, Marrio is gone,” Marquita said.

Mary broke down. She was in disbelief, but when her daughters told her about their conversation with Horn, she knew it was true.

There was so much they still didn’t know. They kept asking investigators for an explanation. Instead, they got conflicting information.

On Oct. 12, a homicide detective went to Mary’s home and told the family that Marrio had an ID on him when he was found, according to the family’s recordings. The detective said he went to two homes believed to be his address, but nobody was there.

“Whatever happened to him, this is February. And this is October. And I’m still getting mail here. But you all are telling me that you all couldn’t find the next of kin,” Mary told the detective, who the family says identified himself as Joshua Johnson, the detective listed in police documents on the case.

“If my son was a person out there that went and committed a crime, you all would have found the next of kin,” Mary continued. “You all would have found him. You all would have come knocking at my door looking for him.”

Mary continued grilling Johnson on the delays.

“Ma’am, I don’t want to tell you all any lies," Johnson responded. "We couldn’t find no next of kin. Nobody was out there."

He told them Marrio’s homicide case was cold, that police had no leads, and left.

One day later, Commander Abraham Thompson, who oversees homicide detectives, visited the family at Mary's home and told them that there was no photo ID on Marrio. He also told them that he’d seen body camera footage showing Johnson leaving a card with his information on it at Mary’s home on Feb. 9. (The Jackson Police Department denied a public records request for this footage.)

Thompson, who identified himself on a recording shared by Marrio’s family, told them that police could have done more to find the next of kin, but that the coroner’s office bore some responsibility as well.

He said the situation made him reflect on what the police department could do better in the future. "I tell people all the time, I'm human, too," he said.

"And my son was a human being," Mary shot back.

"Absolutely," Thompson agreed.

"He was treated like he was a dog in the street," Mary said. "That’s the way he was treated."

Later in the conversation, Thompson admitted that leaving a card wasn't enough to notify the family.

"We could have did better," Thompson told Mary. "I said we could've did a better job at trying to make sure that we stayed consistent and persistent with trying to find the next of kin. Leaving a card in the door? Oh, he might felt that that was sufficient. No, I don’t feel that it is. We could have, should have, kept going."

Mary began the process of recovering her son’s body. She paid $250 to reclaim the rights to his remains. A coroner’s office staffer told her it would cost another $500 to have Marrio exhumed.

The family asked a funeral home for help. A representative warned them that there wouldn’t be much left of Marrio’s remains, just bones in a bag, April, a cousin, recalled.

“At that point, that’s when reality set in,” April said. “Y’all dispose of people’s bodies like animals? Not even like animals, because people do animals better than that.”

The more Mary thought about it, the more upset she grew. “When they dig him up, I’m not going to be able to stand it,” she said. “Once they begin to…”

She became too upset to finish the thought.

Instead of seeking an exhumation and funeral, the family decided to hold a memorial for Marrio without his body. They have not been told where exactly Marrio is buried. NBC News has asked for his grave number in the pauper’s field, but the coroner’s office has not responded.

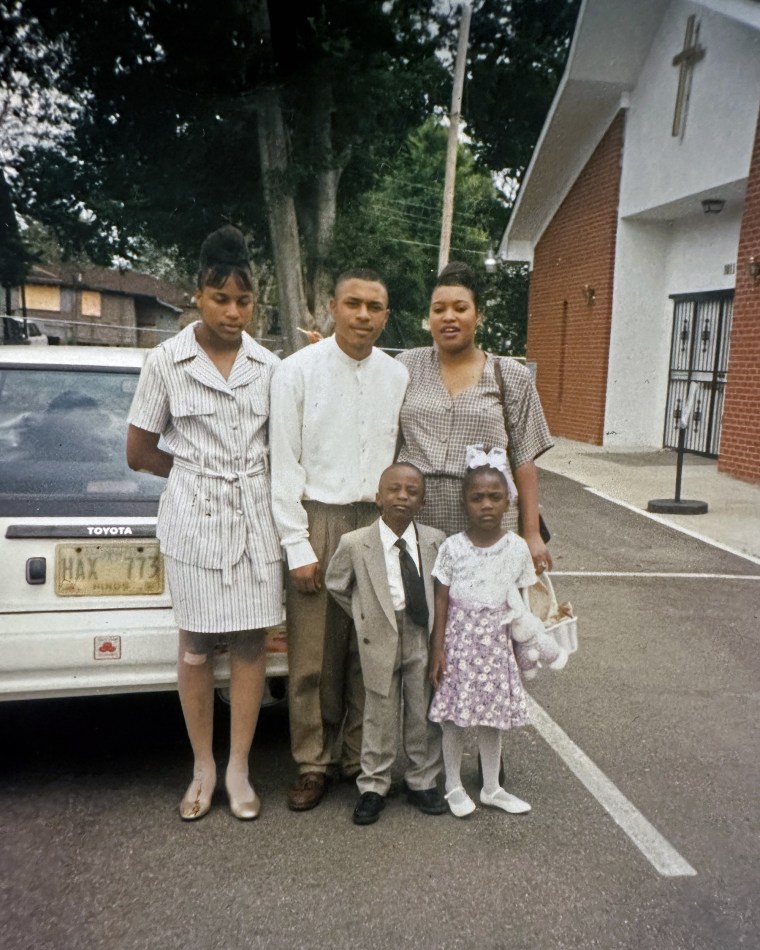

The memorial was held Oct. 20 at Mary’s church, Nu Vision Worship Center in Jackson. A pastor described Marrio as a man who never lost his connection with God. Others recalled his charisma and intelligence and how he drew people into long conversations. The program included photos of him as a boy and as a young man, arms around his mother and siblings, relaxing on his bed. There were tears, but there was also laughter.

Afterward, Mary didn’t go back home with the rest of her family. She and her husband took some time alone to think and try to find peace.

She could not.

“It really didn’t do anything,” Mary said. “Because he was just a picture. It wasn’t the person. The last time I’m going to see him is that picture. I’m not going to see him no more.”

She still wants to know the truth of what happened to her son.

“It hurts bad that he’s gone. But nobody thought that I was important enough to let me know about my child,” she said. “Nobody thought that my family was important enough.”